Self-Directing

Thank you for visiting my blog!

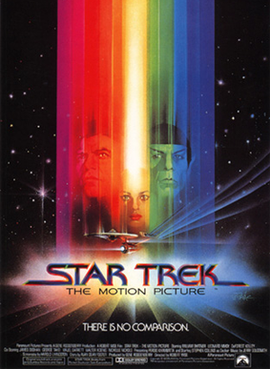

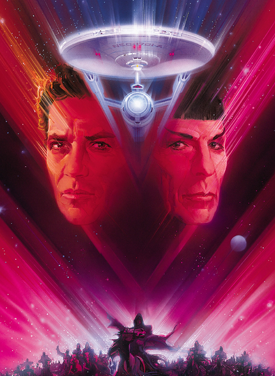

Here I share what I have learned about my passions--teaching, music, and film.

Use the categories and archives features to sort posts.

Let me know what you think [email protected]

Here I share what I have learned about my passions--teaching, music, and film.

Use the categories and archives features to sort posts.

Let me know what you think [email protected]